There’s a particular kind of queer movie that gets marketed as “provocative,” but what that usually means is: look, sex! shock! scandal! Pillion isn’t interested in that lazy lane. Yes, it’s explicit. Yes, it’s BDSM-forward. But the bigger swing is that it treats kink like a lived language – something people use to negotiate desire, safety, identity, power, and, sometimes, vulnerability they don’t know how to name out loud.

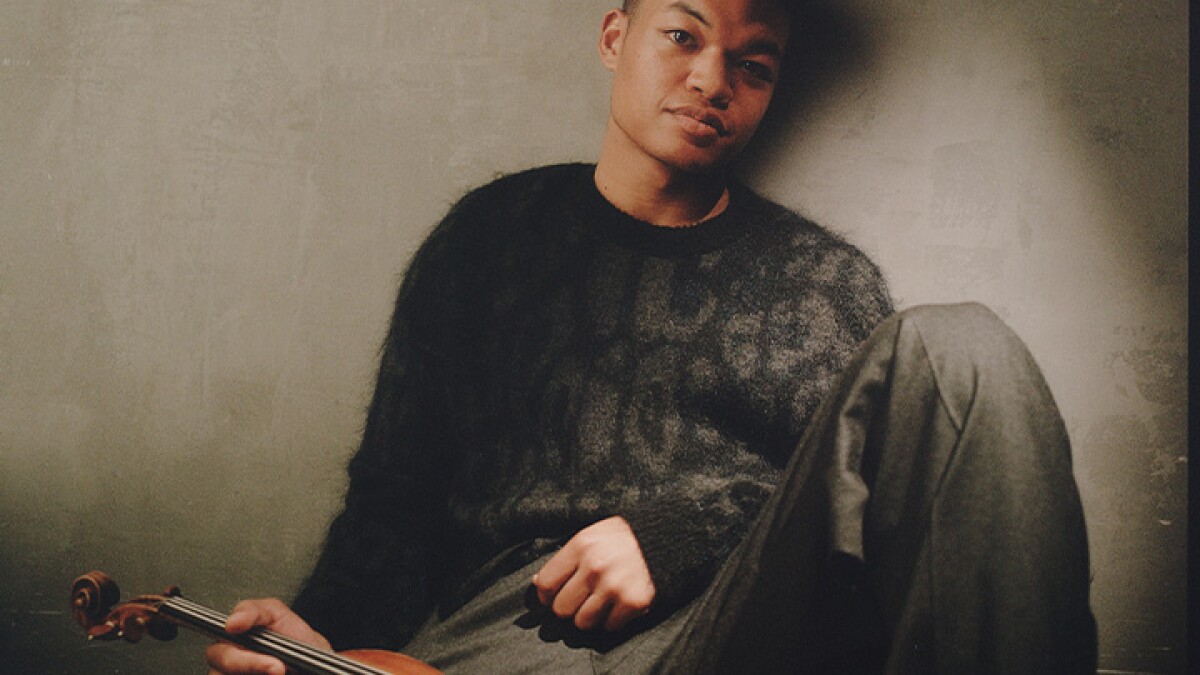

The premise is deceptively simple. Colin (played by Harry Melling) is shy, drifting, and lonely in a way that feels painfully familiar – someone who’s been surviving on crumbs of validation. Then he meets Ray (Alexander Skarsgård), a biker Dom with charisma and a kind of calm authority that can read as intoxicating or alarming depending on what scene you’re in. The relationship that forms is structured, ritualized, and not remotely “standard rom-com.” That’s the point. Pillion wants you to sit in the tension between “this is hot” and “is this healthy?” – and it doesn’t offer easy answers.

What makes the film work is how grounded it stays in Colin’s interior life. Melling gives a performance that’s awkward and raw without turning Colin into a punchline. You can feel the tug-of-war: the thrill of being chosen versus the fear of being used; the comfort of rules versus the ache of not being seen beyond your role. The movie understands that submission isn’t the same thing as invisibility – and it pays close attention to the moment those lines blur.

And yes, Skarsgård is doing what he does best here: commanding presence, controlled menace, a surprising softness around the edges. But Pillion doesn’t let Ray become a fantasy cutout. The film keeps nudging the question: when you’re the one holding power, what are you responsible for emotionally – and what are you refusing to deal with by staying “in character”? That’s where the movie gets interesting, and that’s why it’s sticking with people beyond the initial “ooh” factor.

Another big win is how it treats queer subculture like… culture. Not a sightseeing tour for straight audiences. Not a cringe “edgy” aesthetic. Just a world that exists, with its own codes, bonds, and blind spots. The film doesn’t sanitize the leather/biker energy, but it also doesn’t sensationalize it. It gives the community texture – messy humanity included – and that feels rare in mainstream-adjacent releases.

Now, fair warning: Pillion is not a cozy watch. The power imbalance is intentionally uncomfortable at points, and the emotional stakes sneak up on you. If you want a neat “communication solves everything” story, this isn’t that. If you’re sensitive to dynamics that can read as controlling, it may hit hard. But if you’re open to a film that takes queer kink seriously – without reducing it to trauma, comedy, or spectacle – Pillion is one of the more honest, grown-up entries in the recent wave of queer cinema.

It’s also not nothing that this film arrived with serious credibility: it premiered in Cannes’ Un Certain Regard and won Best Screenplay there, and it later took Best British Independent Film at the BIFAs. That doesn’t automatically make something good, but it does explain why Pillion is being discussed like more than a niche curiosity.

If you’re the kind of Philly queer who likes your stories a little gritty, a little brave, and emotionally real – this is one to catch when it hits local screens. Go in expecting heat, yes, but also tenderness, discomfort, and the kind of aftertaste that turns into group-chat debates.

Premiers in Philadelphia on Febraury 6, 2026